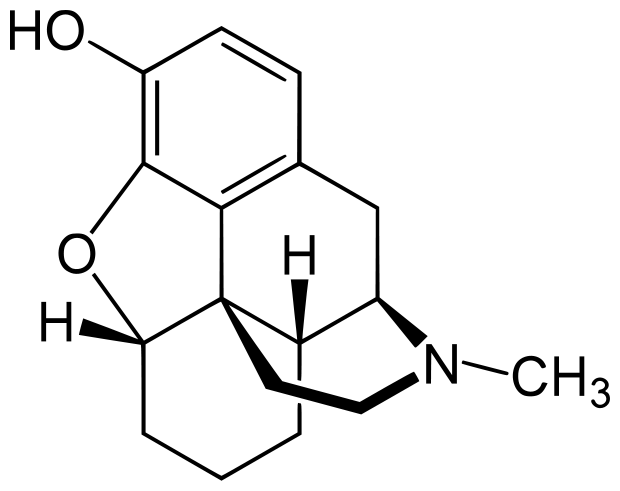

The effects of opioids are primarily due to their action on the mu opioid receptor. Molecules that interact with this receptor can be classified into three primary types, full agonists, partial agonists and antagonists. Full agonists such as morphine or methadone activate the receptor in a dose dependent manner. Partial agonists also activate the receptor, but the activation reaches a plateau and will not respond to increases in dosage. Finally antagonists such as naloxone bind to the receptor, but do not activate it at all.

The two most commonly used opioid antagonists are naloxone and naltrexone. Both are competitive antagonists, which means they work by competing for the receptor's binding site. The strength of the bond between the ligand (drug) and the receptor is known as the affinity. Molecules with higher affinity for the receptor will replace those with lower affinity. Naloxone has a higher affinity for the mu opioid receptor than morphine, when administered it will replace the morphine bound to the receptor. Because naloxone is an antagonist, the receptor will deactivate completely reversing the effects of the morphine.

Both naltrexone and naloxone can be described as substituted derivatives of oxymorphone. The tertiary amine methyl-substituent is replaced with a longer chain of carbon atoms (an allyl group). With naloxone the N-methyl group of oxymorphone is substituted with an N-prop-2-enyl group, with naltrexone this substitution is with an N-cyclopropylmethyl group. The name naloxone has been derived from

N-allyl and

oxymorph

one.

While both antagonists have high oral bioavailability, they both undergo extensive first-pass metabolism. Up to 98% of naloxone is metabolized to an inactive metabolite, and for this reason it must be administered as an injection or intranasal spray. Naltrexone is metabolized to 6-β-naltrexol, which is an active metabolite also acting as an antagonist at the mu receptor. While naloxone is used primarily as an emergency antidote to opioid overdoses, naltrexone has been used as a medication to treat alcoholism and opioid addiction.

Pharmacokinetics

"When naloxone hydrochloride is administered intravenously the onset of action is generally apparent within two minutes; the onset of action is only slightly less rapid when it is administered subcutaneously or intramuscularly. The duration of action is dependent upon the dose and route of administration of naloxone hydrochloride. Intramuscular administration produces a more prolonged effect than intravenous administration. The requirement for repeat doses of naloxone hydrochloride, however, will also be dependent upon the amount, type and route of administration of the narcotic being antagonised. Following parenteral administration naloxone hydrochloride is rapidly distributed in the body. It is metabolised in the liver, primarily by glucuronide conjugation and excreted in the urine. In one study the serum half-life in adults ranged from 30 to 81 minutes (mean 64 ± 12 minutes). In a neonatal study the mean plasma half-life was observed to be 3.1 ± 0.5 hours."

-

Naloxone Data Sheet (New Zealand)

"Naltrexone Hydrochloride is a pure opioid receptor antagonist. Although well absorbed orally, naltrexone is subject to significant first pass metabolism with oral bioavailability estimates ranging from 5 to 40%. The activity of naltrexone is believed to be due to both parent and the 6-β-naltrexol metabolite. Both parent drug and metabolites are excreted primarily by the kidney (53% to 79% of the dose), however, urinary excretion of unchanged naltrexone accounts for less than 2% of an oral dose and faecal excretion is a minor elimination pathway. The mean elimination half-life (T-1/2) values for naltrexone and 6-β-naltrexol are 4 hours and 13 hours, respectively. The elimination half-life and time to maximum concentration are dose-independent. Naltrexone and 6-β-naltrexol are dose proportional in terms of AUC and Cmax over the range of 50 to 200 mg and there is no significant accumulation after 100 mg daily doses."

-

Naltrexone Data Sheet (New Zealand)

Responding to an opiate overdose

Most overdoses are the result of mixing opiates with central nervous system depressants. Although naloxone only works on opioids, it is the synergism of the drug combo that causes the overdose. Removing the opioid component only will usually restore respiratory function. Opiate users should practice assembling the naloxone kit so as to be efficient in case of an emergency. If someone has stopped breathing every minute matters, combined with the stress and adrenaline of the emergency you don't want to have to take time out to read an instruction manual. Since naloxone overdose kits have been introduced in the US, over 10,000 lives have been saved by non-emergency persons (the friends and family of drug users).

If the individual has stopped breathing:

Do rescue breathing for a few quick breaths, then administer the naloxone. Depending on if the naloxone is administered as an injection or intranasally, it may take a few minutes to take effect. If there is no effect after 3-5 minutes, administer another dose of naloxone.

If the naloxone does not work after the second application, something is wrong. Naloxone may not work if:

1. The overdose is not due to opioids.

2. The opioid causing the overdose has a higher affinity for the mu receptor than naloxone, which can happen with some synthetic opioids (such as buprenorphine or fentanyl and its analogs).

3. Too much time has lapsed and the heart has stopped.

"

Naloxone only lasts between 30 – 90 minutes, while the effects of the opioids may last much longer. It is possible that after the naloxone wears off the overdose could recur. It is very important that someone stay with the person and wait out the risk period just in case another dose of naloxone is necessary. Also, naloxone can cause uncomfortable withdrawal feelings since it blocks the action of opioids in the brain. Sometimes people want to use again immediately to stop the withdrawal feelings. This could result in another overdose. Try to support the person during this time period and encourage him or her not to use for a couple of hours."

Further Reading:

Community-Based Opioid Overdose Prevention Programs Providing Naloxone — United States, 2010

Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR)

February 17, 2012 / 61(06);101-105 [

Link]